The U.S. stock market plunged April 4 and 5 as investors expressed grand concerns regarding the potential impacts of global tariff policy announced the Wednesday before. The response being inarguably negative, the primary points we broadly resolved from the days’ trends include:

- Tariffs were more broadly applied at higher levels than expected. To the extent that the rates remain in place, American companies will find profits pressured, while consumers will see higher prices

- Tariffs are not based on country-specific trade-related policies; this lack of basis may confound negotiations

- Tariffs continue to be seen as ill-formulated blunt-force weapons being deployed for stated purposes otherwise more efficiently pursued by a range of other means

- Seeking safety, investors fled to bonds and yields fell sharply. The shift suggests the increased probability of an economic slowdown outweighs investor fears of resurgent upward pressure on prices

- All in, the tariff regime is likely to prove resoundingly negative for the U.S. economy in the near term and perhaps longer, with higher costs and increased uncertainty/insecurity suppressing growth

That’s the Brief

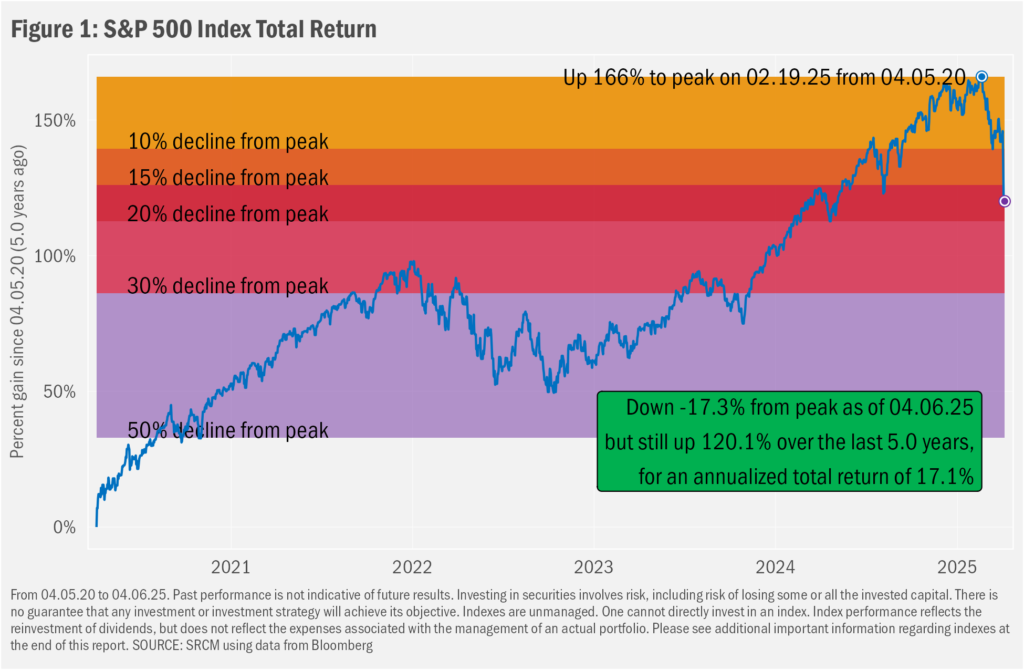

Hearkening back to the COVID-19 era, severe back-to-back declines in the U.S. stock market were its worst since June 11, 2020. The current drawdown of 17.3% in the S&P 500 Index, which began on February 19 of this year, ranks 15th-worst since 1949. The index, which is designed to reflect the performance of U.S. large-cap stocks, is still up 120% over the past five years, a period that begins just a few skips from the bottom of the COVID-19 pandemic drawdown. And that half-decade also includes the 8th-ranked 24.5% drawdown we experienced from early January 2022 to mid-December 2023. After such exceptional gains, one might have expected at some point to see an exceptional decline. But the rapidity of the drop and the folly of its impetus seemingly have stunned global investors, who are left to ponder the path forward for trade policy and investment markets.

Now What?

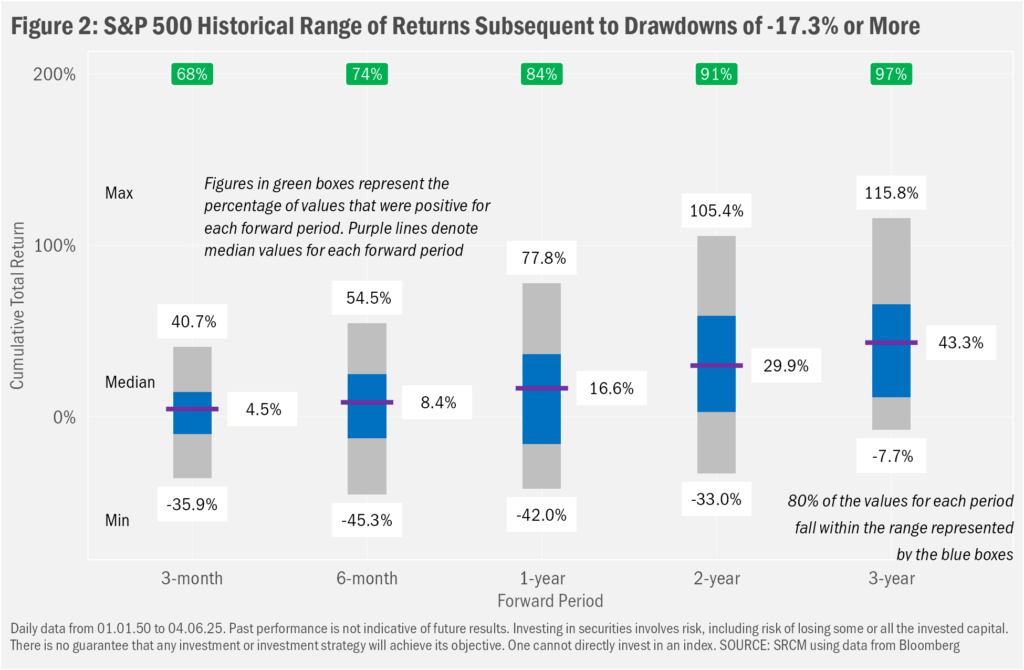

As we always do during market drawdowns, we’ll offer this perspective: so long as one’s financial circumstances have not changed dramatically, sticking to an existing investment strategy historically has tended to have proved the smarter decision. But we know such a quick and substantial drop can unnerve even more seasoned investors. So, we provide the data in Figure 2 with the intention to demonstrate the propensity for returns subsequent to market drawdowns to recover over the medium term. In that chart we show the range of outcomes over various future time frames after we saw a decline in the S&P 500 equal to or greater than the current 17.3%. While history has shown occasions where the market had yet to recover even three years out, the historical probability of a recovery generally has increased with time. That is, as we show in the green boxes, the prospects of a future gain after a drawdown have tended to rise with time. That doesn’t mean a full recovery from the drawdown, however, just a positive going-forward outcome.

A drawdown has three components: the prior peak, the trough (lowest point), and the eventual breakeven (a recovery above the prior peak). While we can hope that we have seen the trough this time around, we cannot be sure. We could conjecture that, as the market “rubber band” has been stretched, we are more likely to be closer to the bottom and that we should expect some manner of recovery, if not all the way back to the February 19 peak. But such optimism might be ill placed, given the events of last week. So, we will note that further losses may well be in store and that, either way, it may take some time for global markets to recover.

Speaking of global markets, on account of a fall in the value of the U.S. dollar and a shift in investor preference for what had been the broadly underperforming shares, international stocks to date have strongly outperformed U.S. stocks this year. The Bloomberg World ex U.S. Large & Mid Cap Net Return Index (which tracks, as the name suggests, stocks outside of the States) is up 1.1% in 2025 through April 4, versus the S&P 500’s 13.43% drop (both in terms of total return, which includes the reinvestment of dividends). Bonds, too, are up on the year, with our preferred measure of U.S. investment-grade bonds, the Bloomberg 1-5 Year Government/Credit Index, higher by 2.54% on a total-return basis. So, certain manners of diversification have been your friends this year so far.

And that means some folks reading this commentary may not have suffered the full extent of the U.S. market’s plunge. Nonetheless, as we already hinted, we may not be out of the woods. Perhaps even far from the nearest clearing. With market futures for the Monday-morning open well in the red, we will remind readers to reach out to their advisors where further context, data and guidance are desired.

Note from the CIO

Regular readers will know that I tend not to editorialize on these pages, meaning I generally prefer to stick to the facts of market history as context for informing optimal investment decisions. Given conversations over the past few days and wishing to ensure that our clients have a firm understanding of our preference for consensus-based theoretical and empirical assessments of macroeconomics and markets, though, I thought it important to provide my own summary of our review of the tariff policies announced last week and their potential implications for trade and investment markets.

I continue to agree with the broad consensus that the immediate effects of the tariff regime will be to put upward pressure on prices and dampen growth. Regarding inflation, some importers will at least partially pass on tariff costs to domestic consumers. And any shift in production to the States likely will result in higher-cost end goods. Meantime, supply chains are likely to buckle in response to the new levies, increasing trade frictions. On the growth front, higher costs generally suppress demand. Where demand is “elastic” meaning sensitive to pricing, consumption likely will fall. Where “inelastic”, higher prices paid will take a greater portion of consumers wallets, leaving less for other goods. As businesses choose whether to absorb the tariffs or pass them along, aggregate demand likely will be suppressed either way. Exports are likely to suffer as trade partners implement retaliatory tariffs.

Given the chaotic presentation and progress of the tariff regime so far, corporate executives are most likely to seek immediate actions to soften negative impacts (e.g., of higher costs they pay as a result of tariffs placed on the imported raw materials they utilize in production), which may include curtailing production, with potential negative implications for employment. The uncertainty of the near-term path of tariff negotiations and the broader economy likely will heighten risk aversion among business leaders. A dampening in expectations for macroeconomic growth will further challenge these more immediate decisions.

Of course, the retort is, “short-term pain for long-term gain!” Were there an actual policy plan to follow that included, for example, the macroeconomic explanations for growth-positive expectations stemming from the tariffs in addition to support for the development of domestic manufacturing capacity, we might follow along. But no such plans have been presented, and most macro explanations offered to date ignore simpler to convey realities.

For example, now that we have decided that such demand should be met with domestic production, we must answer how demand for the imports driving our bilateral trade deficits will be met from domestic production. Neither banana trees nor manufacturing sites sprout from the ground in a matter of days, months and or even years. Until the global tariff structure stabilizes, however, CEOs likely will err on the side of caution, delaying large-scale investments until future trade frictions are more clearly resolved. And over the medium and long term, even if some tariff equilibrium is found, executives are likely to hold off on larger investments for fear the fundamentals may dramatically change over the course of multi-year investment projects. Reciprocal actions may see competitors to domestic manufacturers filling the void left as importers of U.S. goods limit purchases. What a loss for our auto manufacturers, for example, were Chinese car makers to fill the gaps in supply for smaller autos in Europe and South America.

We wonder, too, the potential ramifications for the services side of the trade ledger. During the 70+ years over which the country has seen manufacturing jobs decline as a percentage of overall employment, the United States has risen to the peak of services provision (as opposed to goods production) by its unparalleled capacity for innovation. That innovation has enabled the country to run a trade surplus in services, meaning the value of the services we export exceeds that of the services we import. Comprising more than a trillion dollars annually, exported services are represented economy-wide, with concentrations in travel, financial services, intellectual property, transport and technology. It should not be surprising were tariff countermeasures to be targeted at service-oriented sectors, resulting in another potential hit to growth.

It is true that this shift to a heavier emphasis on services within an economy more dependent on goods shipped from abroad has seen the loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States. And that decline has disproportionately hit certain regions and income segments. But the drivers of those losses can be found here, too. American politicians can be faulted for their penchant for debt-funded fiscal policies as well as tax policies that generally incentivize consumption over savings. And American consumers may be scolded for their fondness for less-expensive goods, while American corporate executives should find blame for their affinity for cheaper labor. All these factors tend to expand our trade deficits in the aggregate.

Would it be great if we made more stuff here in the U.S. in order to reverse some of that decline? I tend to think so. But we are never going to be able to manufacture sneakers, for example, less expensively than can be done in Vietnam. Using humans, at least; much of the discussion in favor of onshoring production fails to acknowledge that automation may limit the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs that might be created. So, we can force production of sneakers here, but American consumers will pay more for them no matter what. Better for us to produce higher-value products—more vehicles, semiconductors and spaceships, as top-of-mind examples—than relatively low-value apparel.

I tend to focus on made-in-America for rarer purchases of more expensive goods where possible, in no small part because the choice tends to reduce my consumption, even as it raises average ticket prices, while generally leaving me with a higher-quality product. But there are only so many items I might need or want that carry a “Made in USA” label. I’m at peace with a higher-value-from-here/lower-value-from-elsewhere mix of purchases, as we simply cannot and should not make everything in America. We certainly can make more things in America, and there are many methods to engender such activity. Tariff bombs are nowhere on that list. Instead of whacking otherwise friendly allies with a tariff stick, which can strike domestic manufacturers can consumers just as hard or harder, we can offer tax and regulatory carrots to establish high-value manufacturing capacity and jobs here in the States. Such approaches are often imperfect, but they can be engineered to be jobs- and growth-positive on balance, as opposed to the everyone-loses features of blunt-force tariff tactics.

I sit on the board of a Pennsylvania-based manufacturing firm that my grandfather helped start in the 1950s. The company continues to grow—expanding our manufacturing capacity and capabilities along with the number of Americans we employ—as our customers find our unique capabilities integral to their continued growth. Experiencing this evolution firsthand is among the greater pleasures of my professional life. As rich as the country is, America should find it easier to incentivize the creation of such businesses by embracing our entrepreneurial spirit than it will by forcing consumers and businesses to pay higher prices while seeking to achieve suboptimal outcomes through brutish coercion.

Braced for More

We’re publishing this note a bit later than expected as we’ve overworked the text above, narrowing our thoughts for concision and clarity, generally summarizing those we’ve found more prevalent among others’ takes, even as we feel we may have insufficiently covered the many threads inherent to the intensely complex study that includes global trade flows and the various policies that guide them. While we’ve presented a critical take on the announcements of last week, we understand that many will disagree, perhaps finding that the only way to dismantle what is perceived to be an unfair system is to break it. It’s clear that investors in the aggregate aren’t comfortable with that approach. Here, again, we will invite readers to reach out to their advisors to discuss portfolio positioning and performance as markets further digest shifting global macroeconomic and geopolitical dynamics.

Important Information

Signature Resources Capital Management, LLC (SRCM) is a Registered Investment Advisor. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any specific level of skill or training. The information contained herein has been prepared solely for informational purposes. It is not intended as and should not be used to provide investment advice and is not an offer to buy or sell any security or to participate in any trading strategy. Any decision to utilize the services described herein should be made after reviewing such definitive investment management agreement and SRCM’s Form ADV Part 2A and 2Bs and conducting such due diligence as the client deems necessary and consulting the client’s own legal, accounting and tax advisors in order to make an independent determination of the suitability and consequences of SRCM services. Any portfolio with SRCM involves significant risk, including a complete loss of capital. The applicable definitive investment management agreement and Form ADV Part 2 contains a more thorough discussion of risk and conflict, which should be carefully reviewed prior to making any investment decision. All data presented herein is unaudited, subject to revision by SRCM, and is provided solely as a guide to current expectations.

The S&P 500 Index measures the performance of the large-cap segment of the U.S. equity market. The Bloomberg World ex U.S. Large & Mid Cap Net Return Index is a float market-cap-weighted equity benchmark that covers the top 85% of market cap of the measured market. The Bloomberg 1-5 Year Government/Credit Index is a broad-based benchmark that measures the non-securitized component of the US Aggregate Index. It includes investment grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate Treasuries, government-related and corporate securities with 1 to 5 years to maturity.

The opinions expressed herein are those of SRCM as of the date of writing and are subject to change. The material is based on SRCM proprietary research and analysis of global markets and investing. The information and/or analysis contained in this material have been compiled, or arrived at, from sources believed to be reliable; however, SRCM does not make any representation as to their accuracy or completeness and does not accept liability for any loss arising from the use hereof. Some internally generated information may be considered theoretical in nature and is subject to inherent limitations associated thereby. Any market exposures referenced may or may not be represented in portfolios of clients of SRCM or its affiliates, and do not represent all securities purchased, sold or recommended for client accounts. The reader should not assume that any investments in market exposures identified or described were or will be profitable. The information in this material may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations, and are current as of the date indicated. There is no assurance that such events or targets will be achieved. Thus, potential outcomes may be significantly different. This material is not intended as and should not be used to provide investment advice and is not an offer to sell a security or a solicitation or an offer, or a recommendation, to buy a security. Investors should consult with an advisor to determine the appropriate investment vehicle.